This Race Report, submitted by Cian Blake, takes us off to Spain. Enjoy the trip....

Everyone watches them out of the corner of their eye. The hotel restaurant is warm yet their unsmiling heads peep out of black puffa jackets as they spill over the sides of the chairs swinging sinewy legs. Retina scorching yellow and pink runners are the only clue to their occupation although the hovering Spanish minder helps. One mechanically delivers slice after slice of unbuttered white bread into his mouth. February 19th is marathon time in Valencia and the Kenyans are in town.

There may be a soul to Valencia but it is hard to find. The town is a montage of shuffling bus station junkies with untied laces, quirky fashion shops down medieval city centre lanes, and stark white modern architecture. The space age Cite de Artes et Science nestles in the old drained river bed overlooked by photocopied blue glass and steel insurance offices. Leaving this is an eight mile run along the river path, through football pitches, fountains, skate parks and a fully functioning athletics stadium, and is done on grass for the entire length. Meals are a mixture of bad value and comedy value – exchanging 25 euros for an Oliver Twist plate of paella a new low.

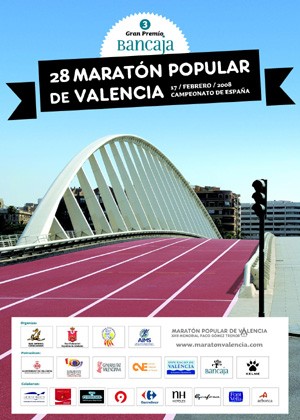

The hotel hums with chatter of the hundreds of mostly Spanish runners milling around the Expo. The Expo is a short name for a long hall with the entry tables at one end and sponsors’ stalls along the sides. All weekend the Bancaja (local bank) and Kelme (shiny football gear) stalls are deserted while crowds surround the Brooks gait analysis treadmill to look at their footprints on the computer. Everyone is slim, stubbly, male and most wear previous marathon t shirts or club tracksuit tops. No Superman costumes here. The five hours time limit ensure amateurs race elsewhere.

Race day and a 6am breakfast. We ram in the bananas like sweat soaked Western Pacific coal stokers and the waitress runs out every 20 minutes to refill the fruit bowl. Nerves peaked the night before but the darkest hour is always just before the dawn. It isn’t any easier with the previous three weeks injury-forced rest so it feels like the night before Leaving Cert Honours Maths with half the revision done.

At the start the atmosphere throbs with chatter underlying the PA announcements. It’s dry and overcast with apologetic clouds in a slate sky not interested enough to rain. The organisers have anticipated everything with a Vaseline stand beside a water stand and the curious sounding Incidences stand. Some genius plays the running-up-the-steps music from Rocky and the only way this can be topped is the Chariots of Fire theme which duly follows. By this stage I have found the 4 hours corral at the back of the bunch and with a minute left the marathon routine starts of jumpers, bin bags and hats propelling themselves into the crowd as runners get rid of them seconds before the gun. The sub 4 hours pacer carries a wooden sign and his sidekick has a red balloon tied to his waist. Their wrinkles and stubble inspire confidence so I decide to stick by them until a few miles to go and see what happens.

Valencia Marathon

The throat clearing first three miles done and my feet will not hit the ground in the order I’d like. Soon this disappears soon and we all get down to business. Desultory crowds stare at us in town but before long we’re in a dusty industrial estate running along a lengthy bin lined avenue, round a roundabout, and back down the other side of the road. This excites no one and there are far more runners than people watching them. The sub 4 man jogs along and Spanish chatter keeps us going. I hear no English unless I have a quiet word with myself. Group running is new to me and by now a slight head wind has got up so I exploit the advantages of it, tucking into the pack and following shoes ahead of me.

Halfway approaches and passes in 2.00.13. This is good so I move slightly ahead of the sub 4 hour pacer’s comfort zone by about 20 yards. We’re back in town now and pass a traffic policeman holding back four lanes of cars stretched down as far as we can see. Every one of them lean on the horns and we cheer this blast of noise. The policeman chews gum and checks his phone.

The talk in the bunch has withered away now - replaced by ragged nasal breathing to conserve second half strength. As my watch hits 2.15 I realise the winner is unlacing his shoes or smiling into an interviewer’s microphone. I’m at kilometre marker 25 which means a water station and I suck it down. The sponge stations are in between the water stations and I use this as a progress marker as the gliding of the first half vanishes and the business end of the race starts.

30k now and still ahead of the four hour man by about a decent back garden. Shouting Spanish children urge us on and wave homemade flags that say “Mama Campeone” in spray paint while their older sisters hold up phones and record our gaping mouths. Nobody chats now and the group has disintegrated. We turn a corner towards Calatrava’s Cite des Artes et Science which looks like a giant Battlestar Galactica helmet discarded on the street. The white concrete surrounding the upper windows seem to merge into the sky and the windows appear to hover a hundred feet up. Ahead of me a four piece band pump out tempestuous flamenco music through blocky black speakers and a runner breaks stride, grabs the lead singer by the waist and dances her across the road before kissing her and moving on. A silver haired lady shielded by a sensible granny blue anorak watches this motionless at the roadside and I realise I’ve seen her before in the first few miles. Is it for a son or husband she shouts Vale Vale (go on go on) or does it fill the silent gaps of her day?

Calatrava’s Cite des Artes et Science

A dismal line of runners’ heads bob for hundreds of yards along the road ahead of me as we approach the first and only hill of the race. Head down trying not to look at the summit and this hill feels like it lasts for an hour. I breast the top and motor down the other side towards a line of traffic held at the side by a stern looking policeman behind coal black sunglasses. Just as I draw level my left leg convulses. Cramp snakes up the back of it like the crack of a whip and I stop with clenched teeth while the policeman barks:

- Vale vale

- I would……I can’t

- Vale vale

- I can’t

Horns wail and beetroot angry heads pop out from car windows. The pain subsides and I walk four steps, jog ten steps, then run and smile and laugh knowing I could have been walking in helpless tears to the end. I revise the under 3 hours 55 target to 4 hours and I’m lucky to be even contemplating that.

Marathon lore: run for 20 miles then race for 6. My thighs burn slowly with each step which reminds me the real race starts here. My stride gets shorter and this alarms me as I know if this continues it will be toddler steps all the way to the end. I push my legs more. They complain but do as they’re told. Previously I gave in to this and finished stumbling. It finally hits me that the marathon is decided out on the lonely course with only thoughts and pain for company and not in the last cheering crowded mile. Canteen chatter of “doing” New York or “doing” Dublin use platitudes to mask the lonely sweat drenched reality of doubt and self examination and perseverance and triumph. Running 26.2 miles is hard. And it’s sore. And it’s worth it. And it’s yours for life - because tear stained aches are soon forgotten in the monumental joy of crossing the finish line to the exquisite sound of the final stopwatch beep.

In the middle distance I can see the tantalising stadium floodlights where we will finish. Marker 38 passes slowly amid more torture for the thigh muscles after their precious few seconds rest. For distraction I start counting back from the 41 kilometres and converting that into miles. Three kilometres to go divided by eight and multiplied by five is around two miles. This figure fuels finish line fantasies of stopping and sitting down. Nothing else bar crossing the line, sitting statue still or lying on the grass if I want. I could lie there all night and it would be perfection because I would demand no more of mile pounded legs. They could rest and I could rest with them and we would all be happy.

Another Irish runner pants into view and we grunt at each other. He has a singlet underneath a shaved head and the pure Dublin accent comes through clenched teeth. I move ahead of him slightly as at the 40k marker a sadistic Spanish lady with a yellow race jacket shouts “Dos kilometres”. What is she talking about? There’s only uno kilometre left!

There isn’t of course and I wordlessly curse myself for this mistake. When I finish this I am past the 41k marker and turning right for the river bed and the stadium. Shouting roadside crowds are five or six deep now and the finish line music is louder and louder. There’s a beautiful down ramp ahead into the stadium running track which I take at full speed nearly hitting another runner who swerves to take his baby from his wife’s arms. My feet hit the soft blue surface of the track. Crowds in the stands cheer and wave. They’re all here to see me I pretend and wave back, so engrossed now that runners ease past me left and right. I ask one more effort from my screaming legs - I get it. They pump more and more and stride longer and longer until we turn the corner into the finish straight and the clock reads 3 hours 56 minutes. One minute later I charge delighted across the line and nearly into a crash barrier. Bent over against it a line of white spit rolls slowly from my leather dry mouth and swings like a pendulum as I stand up to look for my wife in the crowd. No sign so no hug. Spasms laser up and down my legs and I have to move to take off the timing chip. Gasps of agony disrupt my attempts to reach my shoes and sit down until a girl comes over to unlace them. She does so and I sit on the grass. Perfectly still. Perfectly happy.

Cian Blake 2008